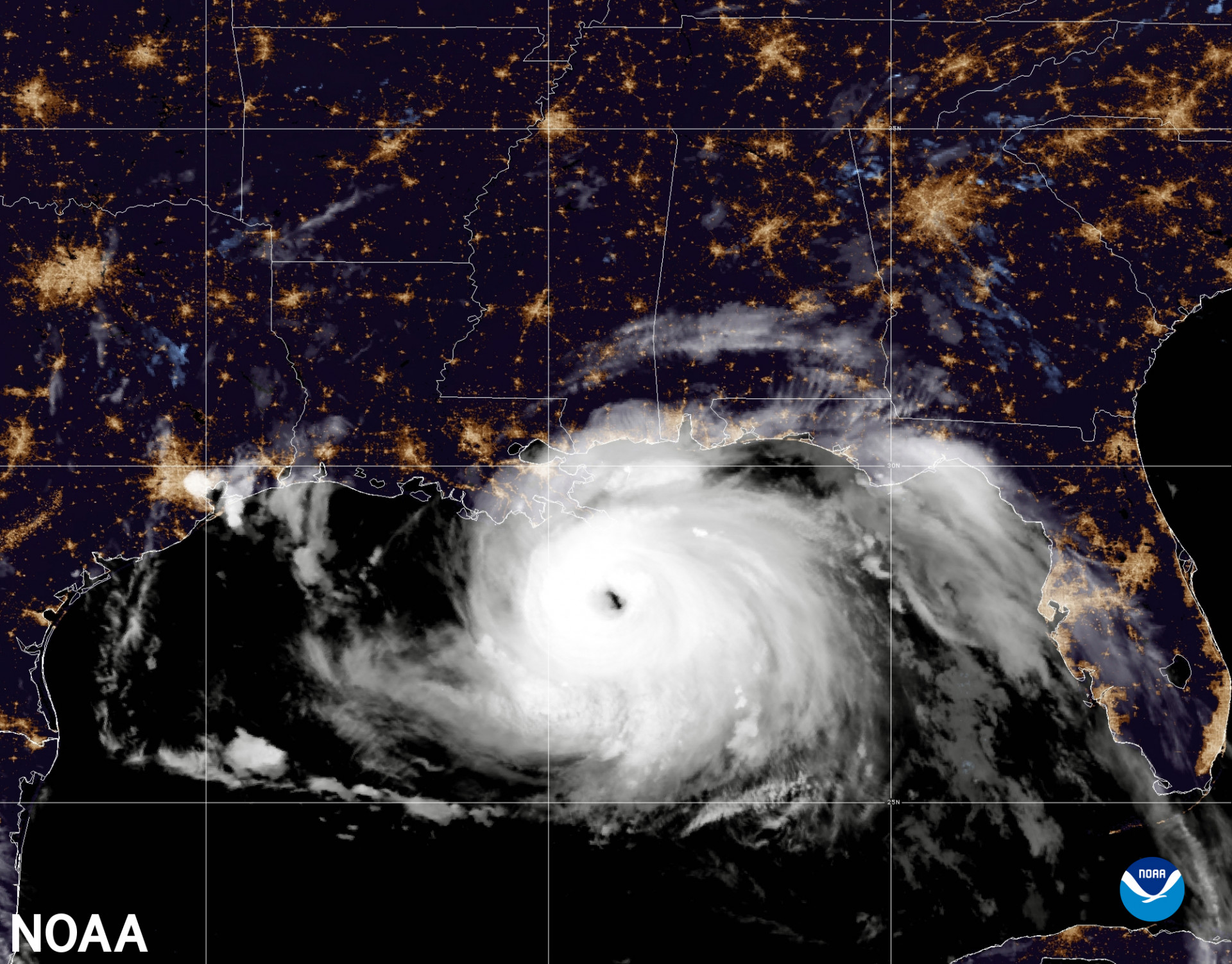

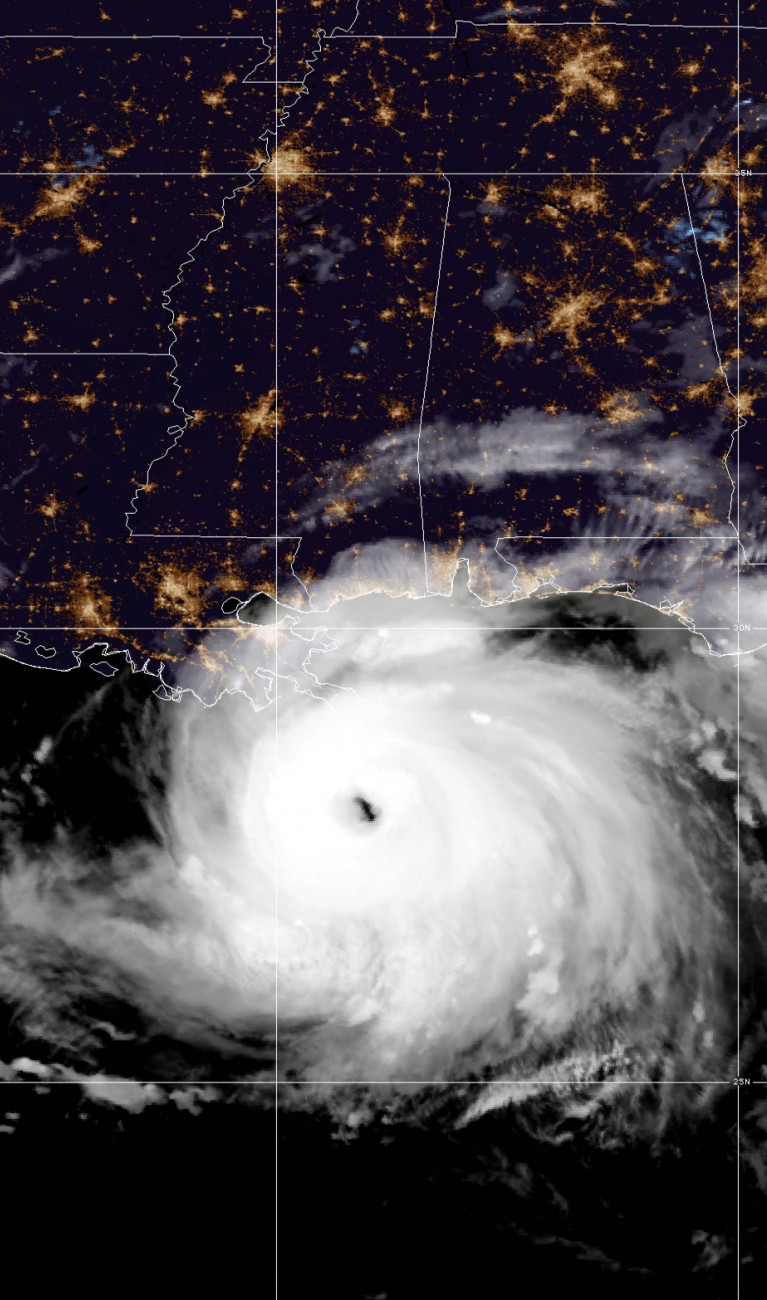

A Caribbean curse

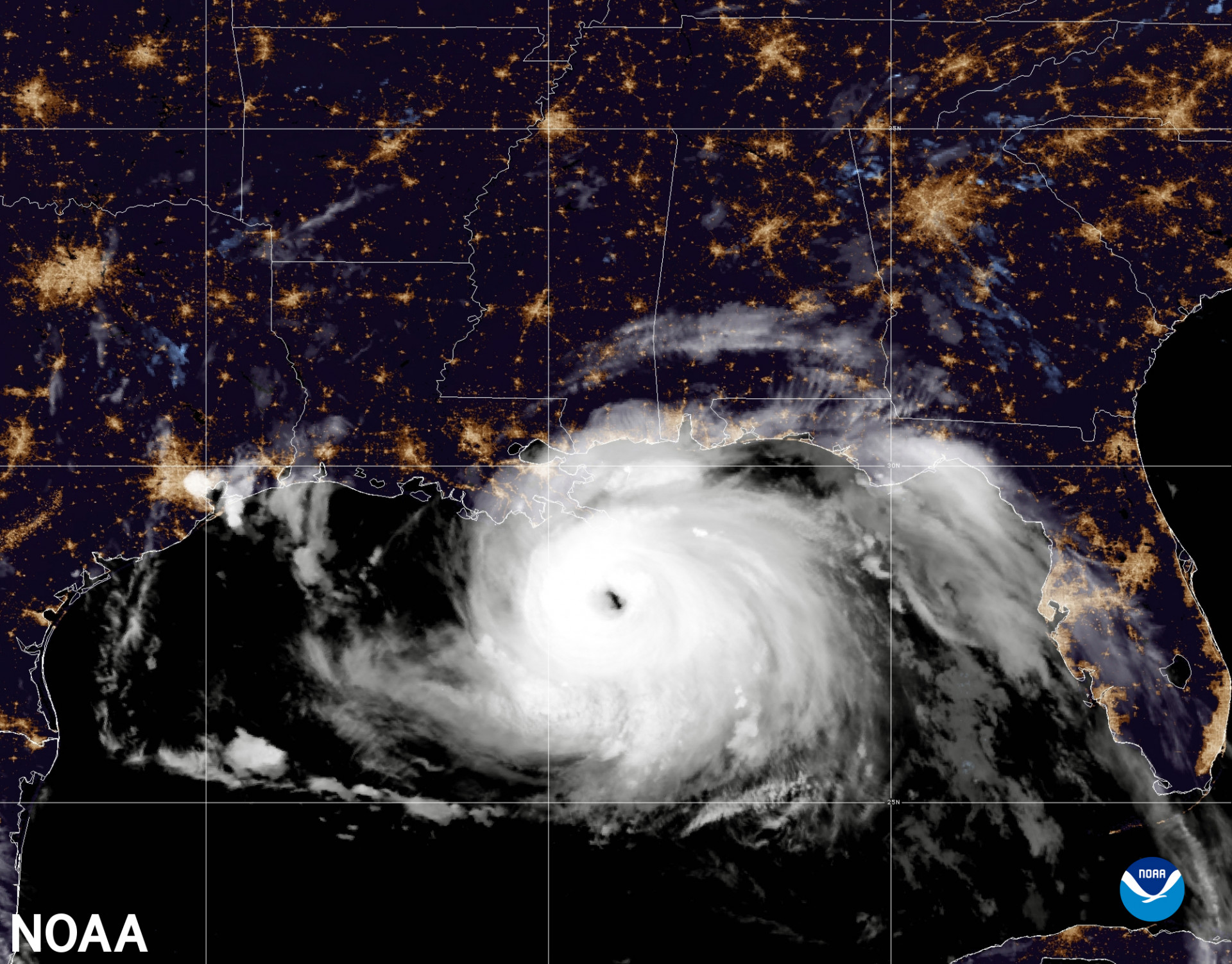

The US weather agency NOAA has just released an alarming outlook for the 2022 hurricane season. According to the report, this year could be an especially intense hurricane year. NOAA cites climate change as the cause.

This year’s hurricane season (June through November) threatens to show above-average storm activity. Up to 21 tropical storms are expected; 14 would be normal. Of these storms, up to 10 are expected to become hurricanes. Three to six of those could even belong to the major categories 3 to 5. Particularly threatening for the southern United States, the Caribbean countries, and eastern Mexico is that the likelihood of a catastrophic super-storm like Katrina in 2005 is also high.

NOAA describes the situation clearly: “The increased activity anticipated this hurricane season is attributed to several climate factors.” These include warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic and the Caribbean, weaker tropical Atlantic trade winds, and an enhanced west African monsoon from which tropical storms develop.

A sea surface temperature exceeding 26°C is needed for the formation of hurricanes. Above this temperature, enough water can evaporate, and water vapor is the actual energy source for these hurricanes. This temperature has long since been reached in the Caribbean and parts of the southern North Atlantic. On top of that come opportune atmospheric and ocean currents.

This combination of currents favorable for hurricane formation is often found in years characterized by the La Niña climate phenomenon, and 2022 is a year in which La Niña is especially prominent. With its influence on global atmospheric circulation, climate change is also playing a role here. Computer modeling shows that on the whole, Las Niñas seem to be getting stronger and last longer. The IPCC’s SROCC report agrees.

So is climate change causing more frequent and intense hurricanes? There is reason to believe this is the case, as NOAA notes that this is the seventh consecutive year with an above-average hurricane season. This kind of frequency is unprecedented.

How much climate is in the weather?

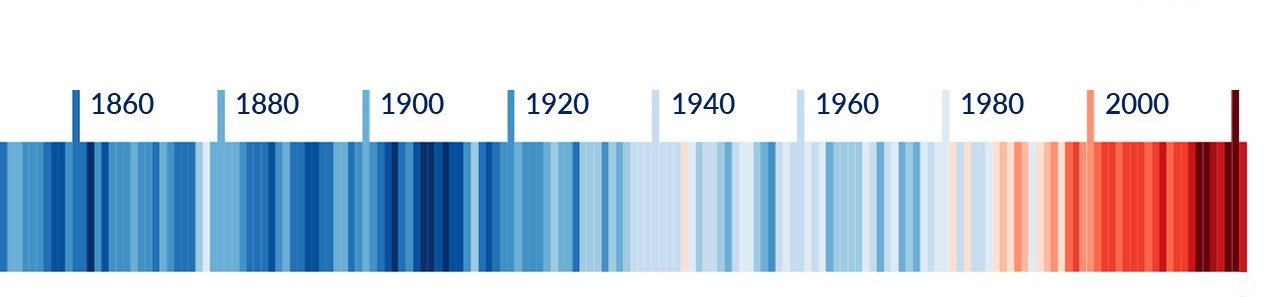

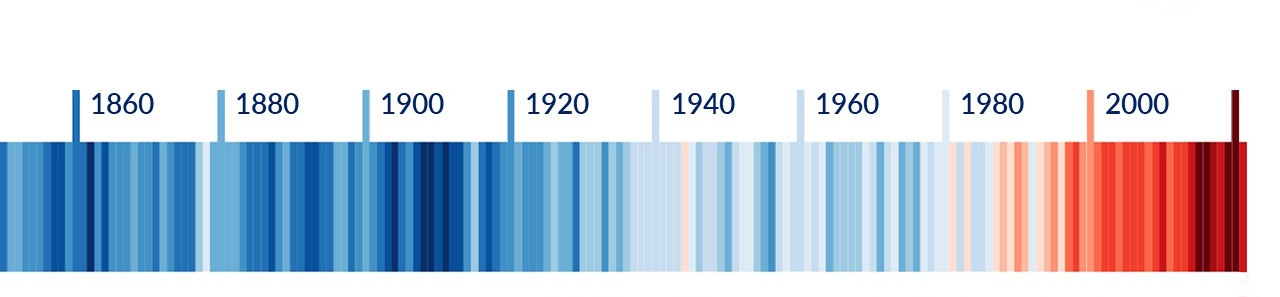

As the current state of the atmosphere at a certain place and time, weather is of course different from climate, which describes the average value of atmospheric parameters over a period of 30 years. The warming stripes devised by climate researcher Ed Hawkins (Figure) clearly show that the global climate has changed dramatically in the past 150 years.

But can we really connect climate change to individual weather events? Yes, we can. A relatively young branch of meteorology called attribution research has been quite successful at doing just that. The pioneer in this field is Friederike Otto of the Imperial College in London, who as co-author of the 6th IPCC report pointed out the connection between weather and climate change. Otto heads the World Weather Attribution (WWA) initiative, which investigates the connections between extreme weather events and climate change. So can we say that 7 percent more water vapor in the global atmosphere means correspondingly more intense weather events?

The current IPCC report does indeed indicate that rainfall has increased by about 7 percent. But things don’t really run in such a simple, linear fashion. “Climate change does not work like a stimulant that is systematically distributed to all of the world’s weather events and heats up the weather by the same amount everywhere,” finds Otto in her book, “Angry Weather.” The Earth's system consists of several subsystems: atmosphere, hydrosphere, cryosphere, geosphere and biosphere. Each of these subsystems is highly complex, dynamic, nonlinear, and subject to both internal and external feedback mechanisms. Climate is the interface where all of these subsystems interact with each other. In addition, humanity is making its presence felt as the anthroposphere has joined these five natural subsystems in the past 150 years.

Thanks to simulation, we now know fairly well how climate works. We’re also beginning to quantify its effect on the weather. As far as hurricanes are concerned, they may not become more frequent, but they will be more intense. On that point, the NOAA, the WMO and the IPCC are very much in agreement.

Atmospheric thermodynamics in a nutshell

A consequence of the law of conservation of energy formulated by Hermann von Helmholtz in 1847 is that the heat energy needed to evaporate water is released again when the water vapor condenses. So cloud formation is nothing more than the release of energy. The spiral clouds of hurricanes and typhoons are an impressive illustration of this transformation of latent heat (hidden in water vapor) into sensible heat, which is converted into mechanical energy in the form of hurricane-force winds.

How does the climate crisis, with an increase in global average temperature of more than one degree in the past 150 years or so, affect these extreme low-pressure systems? Émile Clapeyron and Rudolf Clausius, two peers of Helmholtz, formulated a law showing that the water vapor content of the atmosphere increases by 7 percent for each degree of temperature increase. That means its energy content in the form of latent heat also rises.

Storms and climate in Germany

There are no hurricanes in Germany. But how are changes in the climate reflected in our weather and in extreme weather events?

At the Helmholtz-Zentrum Hereon in Geesthacht, the Coastal Climate and Regional Sea Level Changes department and the Northern German Coastal and Climate Office investigate changes in the regional average sea level, extreme events such as storms and storm surges, and sea states. The Storm Monitor analyzes whether and why strong storms can be expected and how climate change is making itself felt. Here, as for hurricanes, the key question is: Are storms gaining in frequency and intensity?

The initially reassuring answer is that the available data indicate no major increase in storms for the North Sea and northern Germany so far. Storm intensity has not risen significantly either.

Storm surges result from a synergy between storms and sea level. Hereon’s Storm Surge Monitor shows no deviations from the long-term average for the Baltic Sea. But in the North Sea, the climate-induced rise in sea level is having a noticeable effect. As the Monitor notes, “The observed increase in storm surge frequency is mainly caused by rising mean sea levels.”

This is in agreement with the observations made by SeaLevel-Monitor.eu. The global rise in sea levels can also be measured in the North Sea and the German Bight. For example, the sea level at Norderney has risen by an average of about 14 centimeters in the past 100 years, of which 8 centimeters came in just the last 50 years.

How much climate is in storms?

The NOAA data show that the climate crisis can be measured in the weather. What has been measured there for tropical storms is confirmed by the IPCC reports. The picture is more complicated for storms in temperate latitudes, as the Helmholtz scientists from the Hereon-Zentrum show. Here a signal from climate can’t be so clearly identified. But that doesn’t mean climate change isn’t reflected in the weather at all. The Ahr River disaster and its flash flood damage have links to the climate crisis.

The new normal is becoming increasingly uncomfortable. Helmholtz researchers such as climate scientist Hans Otto Pörtner have been pointing out for years that the 1.5-degree target from the Paris Agreement is no bargaining chip. Mother Earth follows the laws of nature and isn’t waiting for international compromises.