Globally speaking, there are still more men than women conducting research, even though the number of male and female students is essentially equal. In part, this is due to a lack of role models. We are looking to change that.

Women have not played an exceptionally prominent role in the history of science. Through much of the 19th century, institutional science remained largely the privilege of white, wealthy men. This was only gradually opened up to women and other marginalized groups by modern universities, when the number of students started increasing in the 1870s.

Even today, with the number of women in many academic disciplines far exceeding 50%, there remains a stark disparity in terms of the proportion of females professionally engaged at higher academic institutions. This can be attributed to a range of factors: the professional career being interrupted for parental leave, the difficulty of combining a scientific career with childcare, the extensive mobility required in the early career, an unequal distribution of less prestigious tasks such as teaching, less significant participation in the development of research projects and a resulting predominance of male-oriented research projects, the impact of unconscious bias, and the lack of female role models.

In the Helmholtz community, equal opportunity is a byword. We use a cascade model to set targets for the share of women at each level of the scientific career. The proportion is determined depending on the share of women represented at the immediately preceding qualification level. In order to specifically promote women, there are various programs, coaching and mentoring arrangements, as well as other opportunities for further education.

These efforts are yielding noticeable results. Even so, the importance of role models should not be overlooked – and there are also many inspiring examples at Helmholtz: International top researchers such as Daniela Jacob, Director of the Climate Service Center Germany (GERICS), Katja Matthes, Director of the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, Antje Boetius, Director of the Alfred Wegener Institute, and many others.

We are featuring a handful of noteworthy female scientists from the Climate Initiative. After all, no two paths are entirely alike.

What is your research about?

My colleagues and I are currently developing the concept for how we want to shape the future of the German National Cohort (GNC). Between 2014 and 2019, the GNC recruited and performed a medical examination on 205,000 women and men throughout Germany. Our intent is to continue and expand the follow-up with the study participants to include genetics and environmental data, for example. The study is ideal for studying the health impact of the great challenges of these days. To my mind, these include the climate crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the aging society with the growing social differences.

How did you get into research?

Three things brought me to science. First of all, I read a book that described the life of a female scientist, and that inspired me as a teenager. Secondly, during my time as a postdoc, I had a great social environment with many people who inspired me. Thirdly, I was fortunate to discover new connections, which gave me the opportunity to keep working.

From the outside looking in, my career would appear to have a linear trajectory: studying in biology and mathematics, which led to epidemiology, then to the evaluation of data in medicine. At times, though, it didn't feel that way to me at all. Today, I am happy about my search, which led me via the Centro Internacional de la Papa in Lima, Peru, and the Harvard School of Public Health in Boston, USA, to being the Chair of the Board for the German National Cohort.

What do you enjoy most about being a woman active in scientific research?

What I like most is the opportunity to craft and implement my ideas and to explore uncharted territory. Basically, I see it as a profession that, in addition to determination, also requires a lot of creativity. Science makes sure that I always have a challenge before me, and the work is extremely diverse. My position today entails just as much management as the further development of very specialized topics.

Working in science is an insecure job – at least until one becomes a professor. How do you deal with that or how have you done so thus far?

In the beginning, I didn't take the uncertainty very seriously because it still was not clear to me at all that I would actually stay in science. At some point, the uncertainty really became an issue for me, and that was once I knew that I was where I wanted to be. Then, I started looking for alternatives and applying for positions. I submitted a total of three applications before being offered my dream position as Director of the Institute of Epidemiology at Helmholtz Munich and as professor at the Ludwig Maximilian University.

How do you manage to strike a balance between such a demanding job and having a private life?

Finding a balance between work and private life is challenging, but I believe it is actually easier in science than in career fields with large personal demands. As scientists, we both have and require self-determination in order to make our discoveries. For me, creativity is a very important facet of being a scientist. My creativity gets a boost in the times reserved for the family and for my relationship with my partner or when I take time out for mountain climbing. Without these things, I would not be able to work productively.

Do you have a role model?

There are many people who have inspired me over the years. When I was doing my university studies in the 1980s, I unfortunately did not have any women as immediate role models. However, my mentors, Erich Wichmann, my doctoral supervisor, Douglas Dockery from Boston, and Bert Brunekreef from Utrecht, made an impact on me and supported me, including in my role as a scientist. Also, importantly, I have made friends over the years in the scientific community, who have inspired and accompanied me along the way.

What would you like to share with young girls and women looking to pursue a career in science?

Being a scientist is a fantastic profession that requires a fair amount of intelligence, willingness to work, persistence, and diplomacy. There are many stages to pass through on the road to becoming a scientist. In my opinion, it is important to make the most of what each stage has to offer. In particular, women should research the things that they find interesting and rewarding. To my mind, this is what’s most important

What is your research about?

I work with the Arctic climate, which is changing at an increasing rate. With the help of climate modeling simulations, we are trying to better understand the processes and feedback effects causing this. I am especially interested in the interactions between the atmosphere and the sea ice. By deepening our understanding and improving our modeling, we can achieve greater precision in simulating the Arctic climate and its changes, which is important for climate impact research, among other things.

How did you get into research?

I have always been interested in the natural sciences, especially mathematics and physics. That said, I didn't want to study them both directly – on the one hand because they seemed a bit daunting, but also because I wanted to combine all the STEM subjects. While looking through the various study options, I noticed meteorology as a specialized subject of physics. That sounded exciting, and my studies did not let me down at all. I was enthusiastic about climate research and it became clear to me that I wanted a theoretical type of work, with numerical models. So, I also did doctoral studies in this area. That said, I didn't manage to find a suitable job afterwards in Berlin, where I moved for family reasons. I decided to prioritize the family, not the research field, and took a job there in biometeorology, where the focus is less theoretical. I actually ended up enjoying this quite a bit. However, three years later, I got an opportunity to return to climate modeling as a researcher: My application at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) was successful. I now work as a senior scientist there.

What do you enjoy most about being a woman active in scientific research?

I enjoy the freedom to work very must as I like. I can choose and develop my own concrete research topics. I like being able to work with many colleagues both in Germany and abroad, meeting them at conferences and exchanging ideas, getting feedback and suggestions, and visiting them during research stays. I also enjoy working with and supporting young people – from interns to postdocs. Also, they have so many good ideas!

Working in science is an insecure job – at least until one becomes a professor. How do you deal with that or how have you done so thus far?

My personal experience was a bit different because I was fortunate enough to get a permanent position at AWI pretty quickly. Today's uncertain research career is terrible. Unfortunately, this has already resulted in losing some excellent young researchers. Keeping science attractive for young people will ultimately require creating fair and transparent working conditions. From my point of view, this also includes a range of alternatives to professorships, such as academic councils or senior scientists.

How do you manage to strike a balance between such a demanding job and having a private life?

For me, this was never just a “job”. There are two crucial things for me: First, there's the very flexible working schedule. When there are tight or short-notice appointments or I am in a “research flow,” then there are times that I work until late in the evening or on weekends. That doesn't bother me too much because I can just work less later. I make sure to have a good work-life balance. On the other hand, my husband supports every facet of my researcher lifestyle.

Do you have a role model?

No.

What would you like to share with young girls and women looking to pursue a career in science?

Science is a truly interesting and exciting career field. If science is what makes you passionate, then just do it and find your way! Do what is important to you and not what others expect of you. Of course, there’s a lot of uncertainty, but pay more attention to the opportunities because they are also out there! And don't neglect your network. It's always a big help.

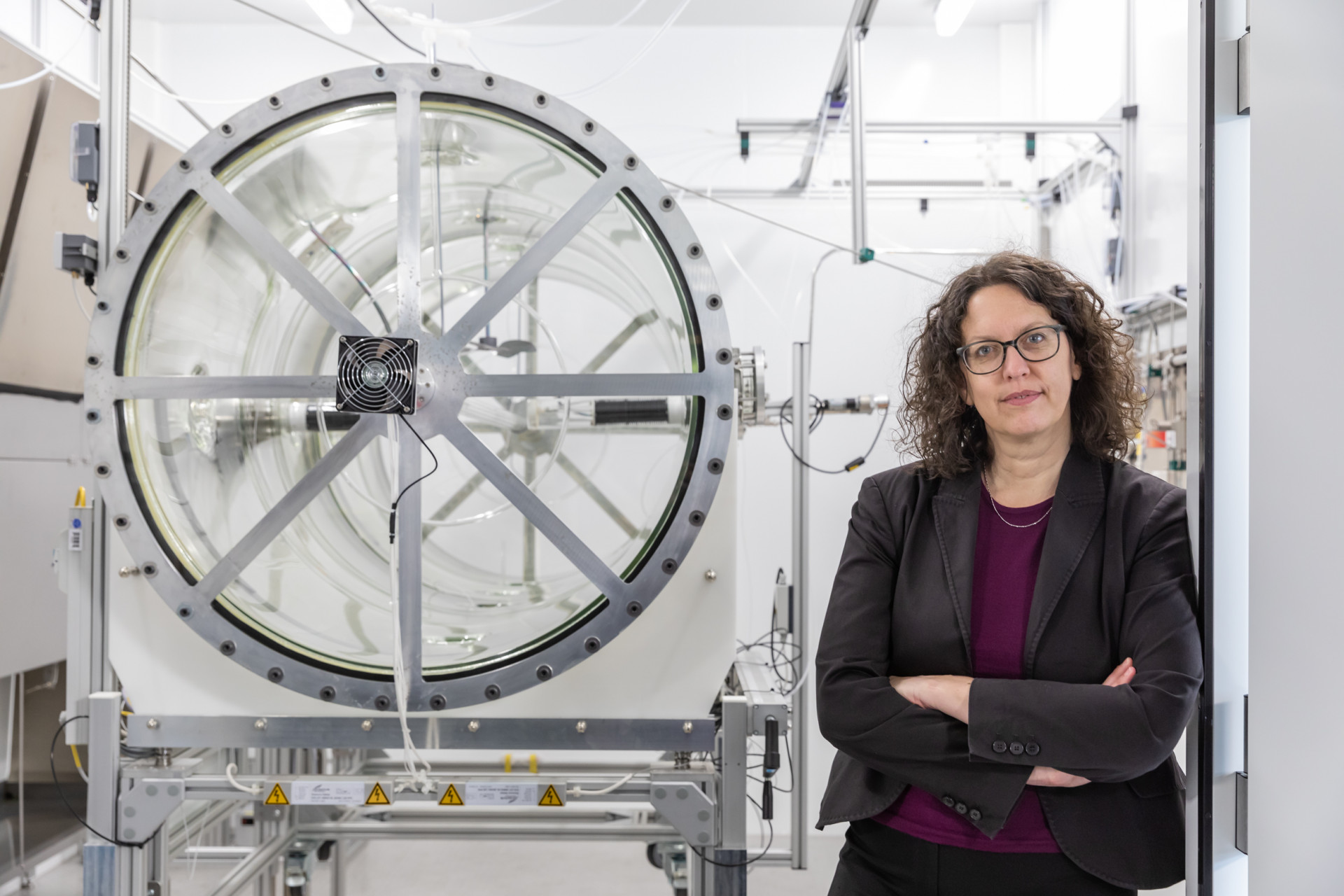

Woran forschen Sie gerade?

Meine Forschung befasst sich mit der Frage, wie Luftschadstoffe entstehen und welchen Zusammenhang es zwischen Luftqualität und Klima gibt. An meinem Institut setzen wir dafür eine Reihe von Methoden ein: wir machen Messungen in der Atmosphäre entweder am Boden oder an Bord von fliegenden Plattformen wie dem Zeppelin und Flugzeugen; mit unserer Atmosphärensimulationskammer stellen wir verschiedene atmosphärische Situationen nach und machen so kontrollierte Experimente; und wir entwickeln Computermodelle, um die Auswirkungen der menschlichen Emissionen auf die Luftqualität regional und global zu simulieren. Mit diesem Wissen können dann gesellschaftliche Entscheidungen zur Verbesserung der Luftqualität und zum Klimaschutz auf fundierter Grundlage getroffen werden.

Wie sind Sie in die Forschung gekommen?

Ich habe Physik studiert, weil ich es für eine spannende Herausforderung hielt und mich grundlegende naturwissenschaftliche Zusammenhänge immer schon interessiert haben. Die Frage, was ich beruflich damit machen werde, habe ich mir zu dem Zeitpunkt gar nicht gestellt. Nach meinem Physikstudium habe ich eine Promotion in der Atmosphärenphysik gemacht und ab dann nicht mehr mit der Atmosphärenforschung aufgehört.

Was gefällt Ihnen am meisten daran, Wissenschaftlerin zu sein?

Wissen zu schaffen im engen Wortsinn – man beginnt mit einer Frage oder einem ungelösten Problem, lernt, was es im Gebiet bereits alles an Wissen gibt, und erweitert dies mit eigenen Beiträgen. Dabei spielt sich insbesondere das experimentelle Arbeiten in unserem Gebiet eigentlich immer in größeren Gruppen ab, die oft sehr interdisziplinär und international zusammengesetzt sind. Ich habe so auch viel über andere wissenschaftliche Ansätze und fremde Kulturen gelernt und weltweit nicht nur Kolleg:innen, sondern auch Freund:innen gewonnen. Mittlerweile in der Lage zu sein, andere fördern zu können, macht mir auch viel Spaß.

Wissenschaft ist – zumindest bis zur Professur – ein unsicherer Job. Wie gehen Sie damit um, bzw. wie sind Sie damit umgegangen?

Ich hatte immer den Eindruck, mit meinem Studium und Können auch für andere berufliche Wege als die Wissenschaft qualifiziert zu sein. Für mich war klar, dass ich den Weg so weit gehe, wie ich ihn interessant finde und dass es auch Alternativen gibt. Dass meine berufliche Laufbahn sich so entwickelt hat, ist die richtige Mischung aus Glück gehabt zu haben und Chancen erkannt und ergriffen zu haben.

Wie schaffen Sie es, einen so fordernden Job mit einem Privatleben zu verbinden?

Da mein Mann und ich beide in der Wissenschaft tätig sind, hatten wir immer viele Freiheiten, unseren Arbeitstag zu gestalten. Das hat insbesondere als unsere Kinder klein waren, sehr geholfen. Diese Zeit war trotzdem sehr anstrengend und wir hatten sicher weniger Zeit für Hobbys und Freunde, als wir das mit einem klassischen „9-17 Uhr“ Job gehabt hätten.

Haben Sie ein Vorbild?

Ein Vorbild im engeren Sinne habe ich nicht, ich bin aber überall dort beeindruckt und inspiriert, wo Menschen unabhängig von gesellschaftlichen Zwängen unbeirrt ihren Weg gehen.

Was möchten Sie Mädchen und Frauen mitgeben, die eine Karriere in der Wissenschaft anpeilen?

Die Meinung anderer zum eigenen Lebensentwurf kann man sich anhören, man muss sie sich aber nicht zu eigen machen.

What is your research about?

Deposits on the bottom of seas and lakes and from dripstones are valuable climate archives. They give us a glimpse into the past, allowing us to better understand the changes currently taking place in the climate as well as to distinguish between natural and human influence. In the “Climate Dynamics and Landscape Development” section at the German Research Centre for Geosciences (GFZ) in Potsdam, we primarily research lake sediments as continental climate archives.

How did you get into research?

This path started for me somewhat by chance in 1977 when I underwent training as a geology specialist at what was called “Central Institute for Physics of the Earth” in Potsdam, where my eyes were opened to another world. After that, I attended evening school for two years to obtain my general qualification for university entrance. Then, I enrolled in geology studies at the Freiberg University of Mining and Technology and started working in the newly established Geochemistry section in Potsdam.

After the reunification, I received a doctoral position at the GFZ and remained in research over the course of various projects. In 2000, an initiative for promoting women gave me the opportunity to establish a lab for stable isotopes at the GFZ – and thus a permanent position. In order to be better suited to run this lab, I switched from geology and geochemistry – concerned with matters far below the surface – to paleoclimate research. That was a big step for me because I had to learn a lot of new things and let go of others, but it was worth it.

What do you enjoy most about being a woman active in scientific research?

I enjoy being able to follow my curiosity and both acquire and apply knowledge – over and over again. The various projects bring me into contact with many motivated and interesting people from other disciplines, allowing me to become peers with them while enthusiastically discovering and developing new things. Plus, there is the field work, which has taken me to many places throughout the world and introduced me to fantastic people.

At least until one becomes a professor, working in science entails a fair amount of professional instability. How do you deal with that or how have you done so thus far?

It’s not always easy to stay balanced. In particular, those who are enthusiastic about their work and also have to constantly prove themselves in order to be able to continue their research often go past their limits. The burden of temporary project-based employment is exceptionally demanding, and it never seems to be enough. There were times when I thought about giving it all up and pursuing something else.

How do you manage to strike a balance between such a demanding job and having a private life?

There are never enough hours in the day, and at times, I can't do justice to my family, friends, or even myself. That means lots of organization, communication, and work on the relationships. On the other hand, it is quite enriching to be able to have so much fulfillment across multiple dimensions of life.

Do you have a role model?

No one per se. I look up to women who listen to their inner voice and follow where it leads – regardless of gender roles and social expectations. Women who question boundaries let their curiosity and love of life carry them where it will, thus inspiring everyone around them.

What would you like to share with young girls and women looking to pursue a career in science?

Don't be afraid to go your own way, even if that means taking a wrong turn or two. Just get back on track, and let your ideas and inspiration take you where they will!

What is your research about?

I oversee a department at the Earth Observation Center (EOC) of the German Aerospace Center (DLR) called “Land Surface Dynamics.” We are a group of 60 scientists whose goal is to quantify the global change being experienced by our Earth. We answer socially relevant questions in the context of urbanization, agriculture, and forestry as well as natural areas worth protecting such as polar and cold regions. How much growth have we seen on Earth in terms of settlement areas and soil sealing? How have the most recent years of drought impacted the forests in Germany? What dynamics in the Arctic, Antarctic, and high mountain landscapes trigger climate change? In order to answer questions of this nature, we use methods of digital image processing and artificial intelligence to analyze extensive remote sensing data – typically long time series of national and global archives. Our results – geoinformation products, facts and figures, findings on causalities, etc. – are shared with science, decision-makers, the media, and society. In my role as a professor, I also supervise doctoral students and regularly give lectures and seminars at the University of Würzburg, where we launched the English-language master's program EAGLE (Earth Observation and Geoinformation for the Living Environment) in 2016.

How did you get into research?

Even as a child, I was irresistibly curious about things related to nature and the environment. At our high school in Bonn, I founded an environmental student club, amongst other things. I've always been fascinated by publications like Geo and National Geographic. At the time, there was no such thing as the Internet. I knew early on that I wanted to study either geography or biology. In my studies of physical geography in Trier and environmental sciences in the United States, I took several courses on remote sensing and also learned quite a bit in various internships. After my studies and fascinating travels, I applied for a position at the German Remote Sensing Data Center (DFD) at the German Aerospace Center, near Munich, where they were performing work using remote sensing to detect underground coal fires in China. As part of this, I participated in numerous field works in Asia and also completed my doctoral studies. Then I had various stints as a visiting researcher and postdoctoral researcher in Beijing and Vienna before returning to the German Aerospace Center. There wasn't one single thing that set me on this path, but I was definitely influenced by my parents, who are very connected to nature, and some excellent biology and geography teachers.

What do you enjoy most about being a woman active in scientific research?

For me, my work is both exciting and full of meaning – after all, we deal rather intensively with the changes taking place on our Earth and also actively contribute to the “Global Transition” dialogue. Society is also calling for quantitative scientific information to cope with the challenges relating to climatic and environmental changes. Furthermore, I have contact with many young people, which is both inspiring and enriching.

At least until one becomes a professor, working in science entails a fair amount of professional instability. How do you deal with that or how have you done so thus far?

Fixed-term contracts were a part of my life for many years and I have to admit that at some point this also stressed me out, especially since my partner was in the same boat at the time and Munich, and its surroundings where I work, are rather expensive. I am very thankful that I took a deep breath and didn't end up switching over to the free economy, where there were multiple options available. For this reason, right away in the first semester, I start giving my students insight into how the German science system works, where there are opportunities of getting good contracts, and how much uncertainty researchers unfortunately still have to deal with when they opt to pursue a career in science.

How do you manage to strike a balance between such a demanding job and having a private life?

Fortunately for me, my work is both a matter of professional and personal interest, and I am often very much in a state of flow. That means that it's OK for me to stay up late at night working on my laptop. In this regard, new home office models at the German Aerospace Center permit a great degree of flexibility. To offset some of this, I also spend quite a bit of time outdoors and use nice time with friends and exercising as a way to recharge my batteries.

Do you have a role model?

There are many men and women that I look up to for their unspeakable commitment, passion, and authenticity. It is truly incredible to witness the energy and empathy that they exhibit in dedicating themselves to “their thing” – mostly for the benefit of our fellow humans and environment. One example of such would be the behavioral scientist Jane Goodall.

What would you like to share with young girls and women looking to pursue a career in science?

Be courageous and confident, and make your dreams come true. It is much easier today than it was 20 years ago to pursue a career in science as a woman. In this respect, there have been many changes for the better. Find yourself mentors who will support you along the way. For example, I always had unconditional support from my doctoral supervisor and institute head, who have always been very supportive of women. In this sense, I was exceptionally fortunate. Build up networks, look for “the good folks,” and if you aren't getting the support that you need from your surroundings, maybe it's time to find another institute or location where the work-life balance and equal opportunities are higher priorities.

What is your research about?

In my research, I explore human-environment interactions. My focus is on allergic diseases and the way that humans and the environment interact at physical interfaces such as the lungs or skin. Similarly, I concentrate on how climate change impacts this dynamic. To my mind, it’s important in light of the climatic changes to understand how embedded we as humans are in our environment. Humans can't be healthy without a healthy planet. We need to see humans as an extension of planetary health, in order to ensure a sustainable existence for us on this planet.

How did you get into research?

Essentially, my coming to science was by chance. My original intention was to study dermatology. That, however, also involves some science. Obviously, I somewhat enjoyed that.

There were naturally some drawbacks, as is the case with all career paths. Luck is also important – but perhaps it’s more the key to overcoming obstacles, managing not to be overly attached to something when a door closes, and taking advantage of the opportunities that come your way.

What do you enjoy most about being a woman active in scientific research?

I’ve always been fascinated by the possibility of exploring clinical issues in research and then, the other way around, taking the scientific results back to the clinic in order to use our findings to offer direct assistance to humans. Here in Augsburg, I have the opportunity to see patients in the outpatient clinic and then take the issues that arise back with me to the laboratory – and vice versa.

For me, environmental medicine is, above all, about enabling prevention. My goal is to prevent diseases, so that perhaps one day allergists will no longer be necessary. Just imagine that for a minute... Or to put ourselves in a better position to adjust to the reality of climate change.

Working in science is an insecure job – at least until one becomes a professor. How do you deal with that or how have you done so thus far?

That has never really been an issue for me at all. My only interest was in doing work that satisfied me. As a medical doctor, you always have the option of practicing medicine, if things don't pan out in the scientific career field. I have always enjoyed working with patients, and that remains true to this day. Perhaps, doctors simply have a pretty fortunate position in the scientific world.

How do you manage to strike a balance between such a demanding job and having a private life?

Early on in my career, a female colleague posed the same question to me, and I answered, “Pretty well!” When she asked how often I see my friends, I gave her a puzzled look. The thought had never occurred to me that I might not have so much time for certain things, because the quality of my relationships was always more important.

I think that, for one thing, society should professionalize childcare and not just rely on help from grandparents, for example. Of course, that takes money. The second factor is your choice of a partner because it’s essential to have someone at your side who's also pulling their share of the weight. And, above all, you have to want it! One way or the other, this will entail compromises and saying no to certain things. If you truly enjoy your work – for me, this is true – then this isn't such a problem.

Do you have a role model?

In a personal sense, I have considerable respect for my mother. An incredible woman! In a professional sense, there was a surgeon that I met when I first started my medical care residency, Ortwin Ruland. I was greatly impressed by the way that he practiced medicine and dealt with patients. Far from being the demi-god in a lab coat, he viewed them as partners on the path to recovery. After that, I was actually thinking of becoming a surgeon. And in a scientific sense, my mentor during a time abroad in Italy comes to mind.

What would you like to share with young girls and women looking to pursue a career in science?

Do it – just do it! As a woman, it’s important to simply never lose sight of the fact that it's also possible. At the same time, you need to be quite willing to face difficulties because there’s no other way to put it: Quite simply, it’s difficult and sometimes even painful. As a mother, it’s important to see that you don't need to do everything. There are things that other people can do for you, and everything can still run smoothly – even without you. Sometimes, that’s a painful reality. But at the same time, you can be happy about it and work on your own plans and dream

What is your research about?

I am a meteorologist and senior researcher at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI). In our “Atmospheric Physics” section in Potsdam, we explore climate changes in the Arctic and how they affect our weather and climate in the mid-latitudes, as well as their extremes. Our specific aim in such is to better understand the fundamental atmospheric processes. This is crucial in order to be able to more reliably project future climate changes in the mid-latitudes.

How did you get into research?

My journey to research began at school. From an early age, I enjoyed and was very interested in mathematics and natural sciences, participated in math olympiads, and was able to attend a class from the 8th grade onward with a focus on math and the nature sciences. This give rise to my desire to study meteorology. My studies were also a great source of enthusiasm. Particularly in the phase of my diploma thesis, I was able to participate in expeditions and assess the collected data in my thesis. For this reason, upon completion of my undergraduate studies, I decided to continue this scientific work in the form of doctoral studies.

What do you enjoy most about being a woman active in scientific research?

It is fun to come up with your own research questions – both individually and in a team – and to develop the methods appropriate to answer these questions and thus to better understand the connections between Arctic climate changes and the weather and climate “on our doorstep.”

At least until one becomes a professor, working in science entails a fair amount of professional instability. How do you deal with that or how have you done so thus far?

When I was just starting my career in science, during my doctoral and first postdoctoral position, I was OK with working in temporary positions. My intent was to get to know various working groups and also to find out if I really wanted to be a scientist. Later, I was quite lucky to be offered a permanent position after 3 years of postdoctoral work. Even today, I remain grateful for the fact that I am allowed to conduct research on the polar climate and the changes it is undergoing.

How do you manage to strike a balance between such a demanding job and having a private life?

I always try to find a good balance between phases of intense work and enough time for my family and friends. I know that my work as a good scientist depends on this. Thanks to my network of friends and the fantastic support from the head of our working group, I was able to continue with my scientific work even when my daughter was quite young.

Do you have a role model?

I don't have one single role model, but I am always impressed when women pursue their own path – however many detours there may be along the way – without simply looking to satisfy the expectations of others.

What would you like to share with young girls and women looking to pursue a career in science?

If you enjoy discovering new things and want to better understand the ties that hold things in nature and society together, then seek out exciting projects and see whether you’re energized by scientific work.

What is your research about?

My group and I investigate the microphysical and optical properties of atmospheric ice clouds. We operate complex measuring instruments mounted under the wings of research aircraft and participate in international measurement campaigns in various places around the Earth. In doing this, our aim is to better understand the ice clouds as part of our climate system and hopefully improve future climate forecasts.

How did you get into research?

I decided to become a scientist when I was 12 years old – after my very first physics lesson. I never lost sight of this goal. After I graduated from high school, my parents did briefly ask whether I would prefer to study law or medicine in order to have a secure job, but the field of natural sciences is what convinced me. It was later on at the university that I found my field in atmospheric sciences.

What do you enjoy most about being a woman active in scientific research?

For me personally, it’s very important to be solving problems, challenging myself every day, and discovering new things. I am also motivated by doing something important for society. Being a scientist is completely different from other careers. We have quite a bit of freedom, but also a lot of responsibility. We are on our own in finding the way to solve problems, and sometimes we have to formulate the question ourselves before investigating it for years on end.

Working in science is an insecure job – at least until one becomes a professor. How do you deal with that or how have you done so thus far?

I am certain that research is what I want to do. So, uncertain employment relationships do not really weigh on my thinking. When thoughts like this come, I tell myself that I have already come so far and should not worry about my future. Women should give themselves more credit and be more confident.

How do you manage to strike a balance between such a demanding job and having a private life?

Since science is also my passion, I generally enjoy my work. At times, there are phases where it is more exhausting – for example, during field measurement campaigns – but afterwards, I can work in a more relaxed manner. Science gives me that freedom. Now that I am a parent, I sometimes wonder whether I am around enough for my son. Even though I don't have a 9-5 schedule in science, I do need to be intentional about taking breaks from it. Now, I spend my evenings and weekends with my family.

Do you have a role model?

I look up to all women who have managed to build a career in science and – despite their success – support younger women starting off in their own careers. As women, we should give each other much more help and support. Men do so, too.

What would you like to share with young girls and women looking to pursue a career in science?

Just be yourself, and don't try to conform. Science needs more women, particularly in physics and engineering.

What is your research about?

In my work, I investigate how an increase in global temperature affects water flows as well as the growth of plants and the transport of carbon and nitrogen into the groundwater. Specifically, I assess data collected on soil cores with measurements obtained from “lysimeters.” Among many other things, these lysimeters measure the amount of precipitation, evaporation, infiltration, and the concentration of nitrate and ammonium. Some of the lysimeters were moved from higher locations to lower ones. In this way, the soils are exposed to different precipitation conditions and a higher temperature. This approach allows investigating the impact of higher temperatures on ecosystem processes, which in my case is grasslands. This is important, not only in order to observe changes in the water balance or the plant composition, but also in order to be able to better estimate the economic consequences of climate change – for example, for agriculture.

How did you get into research?

This was not my original plan. My parents are not academics, so there was no expectation that I definitely needed to pursue university studies. While studying geography, I was particularly attracted to topics about water and climate change. I wrote my thesis in this subject area at a research institute, where I now have returned to work after being in many other stations in my career. During this time, I realized that I am very interested in environmental research. There wasn't any single "trigger." One thing’s for sure: I’m fascinated by always dealing with some new question, learning new things, and trying to understand the interrelations. It’s also possible that the intensity and enthusiasm, as well as the openness and helpfulness that I saw in my former colleagues and my supervisor were somewhat contagious.

What do you enjoy most about being a woman active in scientific research?

You never stop learning and dealing with new aspects of your discipline. There are tons of opportunities for exchanging ideas with colleagues – and on very different levels at that. You also always have the opportunity to work with university students or classes with school children. I enjoy doing that and think that it's important to talk about my work outside of my own research community as well.

Working in science is an insecure job – at least until one becomes a professor. How do you deal with that or how have you done so thus far?

For me, this lack of certainty is very stressful. For this reason, I cannot entirely rule out that I will someday leave science.

How do you manage to strike a balance between such a demanding job and having a private life?

I try not to let work into my free time – and vice versa. Otherwise, you are never really doing one thing or the other. Since I have children, I have a relatively set schedule for work anyway.

Do you have a role model?

I don't have a specific role model, but I have met many colleagues that I admire for their creativity, power, and passion. Also, during my doctoral studies, I was quite fortunate to receive support and encouragement from my supervisor and other colleagues. They gave me a lot of freedom, but they also asked critical questions at the right moments to keep the focus of the work in perspective. In some cases, I quickly got thrown into the thick of it – for example, when it came to writing grant applications, getting initial teaching experience, or participating in specialized committees. However, they have always supported me and had my back, and I have now grown into many tasks. If you look back a bit further, I am fascinated by researchers who had the courage to go beyond what was commonly considered conceivable at their time.

What would you like to share with young girls and women looking to pursue a career in science?

That they shouldn't let anything keep them from pursuing this goal. You shouldn’t let poor overall conditions scare you off. Instead, you should consider whether you are willing to accept the uncertainty and the all-but-clear prospects. After all, science is not a one-way street. An academic education can also lead to interesting alternative career paths.

What is your research about?

I work with ice cores from Antarctica and Greenland. We use various parameters that we measure on the ice cores to investigate how the climate changed in the past. Compared to today, how big were temperature fluctuations in the past? How do volcanoes, atmospheric circulation, or local processes influence our climate time series? In order to explore these questions, we analyze many surface samples, short snow profiles, and ice cores. These analyses are crucial in order to classify the changes and extreme events that we're currently experiencing.

How did you get into research?

When I was young, polar research had already piqued my interest, and I read books about expeditions and polar explorers. From an early age, I wanted to “get to the ice.” I chose my field of study because of a radio report featuring a geophysicist who reported on his work. After starting with geophysics and then a period of study abroad on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen, I finished with a degree in earth sciences. I then wrote my thesis in glaciology at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) and at the Cold Regions Research and Engineering Lab in the USA and then completed my doctorate at the AWI. After that, I had enough of pure research and worked in scientific communication for a good two years. But my longing for research and the wanderlust for the ice was stronger. At that point, I filed a DFG application which allowed to me continue my own research.

What do you enjoy most about being a woman active in scientific research?

Naturally, the best part is the actual scientific work: analyzing, understanding, and contextualizing the data. I try to keep that spirit alive, even if there are more administrative tasks now.

I enjoy the challenge of always opening my mind further, as well as reading, learning, and interacting with other people. That way, your brain doesn't get rusty.

I also believe that scientists have a considerable social responsibility as educators and communicators. I not only enjoy these roles, it’s a matter of personal importance to me to contribute in this manner.

Working in science is an insecure job – at least until one becomes a professor. How do you deal with that or how have you done so thus far?

When you're just starting off as a doctoral student and postdoc, it doesn't seem all that important. If nothing else, I managed to handle it pretty well for a while. In between, I had a position that was set to be extended for an unlimited time, but I really didn't like it. So, I decided not to stay. However, there eventually came a time where I realized that I didn’t want to be in the “I still have to learn everything” mode anymore. I wanted to help shape the work, contribute my skills, and be involved in the decision-making. I gave myself a deadline – either everything pans out with this application and I get this permanent position or I leave scientific research and look for another possibility. I was given the position.

How do you manage to strike a balance between such a demanding job and having a private life?

Throughout the years, my partner has given me the support and freedom necessary for me to do my job. Especially if you have children, this is not possible without a joint effort. Last but not least, the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated that at the end of the day, as a family, you somehow have to find a way to balance work and children – for both parents to able to work, they have to be on equal footing in the relationship.

Plus, I also have the good fortune of working in a fantastic community. Among those working with ice cores, there are a lot of fantastic, strong women, especially from Scandinavia. In those countries, the question as to whether children and family can be combined with the rest of life never even comes up.

I am intentional about including breaks into my daily routine. Whether in the evening, on weekends, or on vacation, family time is family time and leisure is leisure. This gives me a lot of strength and energy to keep going in my job.

Do you have a role model?

There are a lot of people that I find inspiring and encouraging – both women and men. I’m quite grateful to two professors who supported and strengthened me a lot on my way, Prof. Dr. Mary Albert from the USA and Prof. Dr. Katrin Huhn-Frehers from Marum. My closest colleagues are often also role models for me because in our joint work, they bring in good ideas, curiosity, and humor.

What would you like to share with young girls and women looking to pursue a career in science?

There is no perfect way to ensure success in science. When we permit diversity, I believe that we benefit – not just in a human, but also in a scientific sense. I would like to encourage people to get involved. Don't let obstacles and setbacks take you off your path. Get in touch with women in your community – whether that be via PhD and postdoc networks or mentoring programs. The most important thing for a woman is that she should love what she is doing.

What is your research about?

My work deals with the spread and effects of plastic pollution, especially in the Arctic Ocean. Of all the global environmental problems, this is one of the most serious ones, and even though we know that plastic waste is everywhere, we still need more data. The Arctic Ocean is very sensitive and plays a crucial role in the Earth's climate. In light of this, any information on such as intense a stress factor as plastic pollution would allow us to better evaluate the current and future effects.

How did you get into research?

I am a relative newcomer to scientific research. I was actually a computer engineer, a field where I worked for more than a decade. The oceans have always been a passion of mine, so eight years ago I decided to study environmental science and participated in an Erasmus Mundus program in Europe. Given my passion for the oceans, I decided to do something about the plastic pollution in the seas, and I reached out to my supervisor Melanie Bergmann at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) for my master's thesis.

What do you enjoy most about being a woman active in scientific research?

Personally, I really like scientific research. It’s my thing. I enjoy taking an interdisciplinary look at issues from different angles in an attempt to solve them and understand nature. Then, there’s the expeditions. I must admit that participating in a research expedition was the most amazing experience that I've ever had.

Working in science is an insecure job – at least until one becomes a professor. How do you deal with that or how have you done so thus far?

This is a very complicated and depressing issue. Up until now, I have been fortunate to have opportunities with the AWI, which allow me to continue my work. Since this is my second career, though, I am closer to retirement than many other junior scientists, and I do not want to deal with the stress of fixed-term contracts, I have decided to return to my home country and ponder my next steps. In my opinion, many scientists are much less productive when every few years, they and their superiors have to dedicate multiple months to working on new proposals in order to drum up a budget for continuing their work. This obstacle even leads to some people leaving science. To be honest, the thought has crossed my mind: Do I really want to subject myself to this for the next ten years and deal with all the stress?

How do you manage to strike a balance between such a demanding job and having a private life?

Up until now, I haven't managed to do so. But I should say I'm still working on my doctorate, and maybe things will change once I've completed my studies.

Do you have a role model?

The people I work with. I truly enjoy the working environment in the scientific community. Experienced scientists look at problems as something that needs to be solved and not as a reason to give up.

What would you like to share with young girls and women looking to pursue a career in science?

If you love science and “playing” with data, like I do, this is definitely the path you should take. Despite all the challenges, I am very satisfied with my work in science. Yes, there are specific problems, but all professions have multiple issues of their own. You should first understand these challenges and prepare yourself for them.

What is your research about?

I am a senior scientist at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) in Bremerhaven. My main research topic is understanding and predicting extreme events such as droughts, flooding, and heat waves. To this end, I try to combine complex data sets such as observation data, proxy data, and the results of climate models. I also try to look to the past – for example, with the help of proxy data such as tree rings, coral, and lake sediments – in order to understand the current climate fluctuations and prepare for the future. In addition, I am responsible for the maintenance and further development of a statistical forecasting tool for predicting the discharge of Germany’s most important rivers. I think that the work I do is quite important not only for science, but also for society in general, since everything about these extreme water-related climate conditions is on the rise – their frequency, their scale, and the associated damage. Researching, understanding, and predicting hydroclimatic extremes is therefore both topical and crucial for society and the economy.

How did you get into research?

My goal actually wasn't to become a scientist. In Eastern Europe, where I am originally from, research has never been a priority. I consider myself quite lucky to have met various people throughout my life who have helped me find my way – and at just the right time. For the first 18 years of my life, I wanted to be a police officer. For one reason or another, my thoughts changed when I was graduating from high school and my physics teacher suggested that I should pursue studies in physics because I was good at it and could always find a job as a physicist. I followed her advice, and I think that was the best decision I have ever made. In the final years of my undergraduate studies, I discovered meteorology, and ever since, I have been literally in love with my profession. However, it has not been an easy journey, and there were times when I really wanted to give up. Being a woman in science – moreover, a woman from an Eastern European country – can lead to both mental and physical challenges, and quite fundamentally so. What has kept me going all these years has been my passion for meteorology and everything that goes into it. I have never thought of my hand as just a job. When you love what you do, it ceases to be a job. Instead, it becomes an integrated part of life.

What do you enjoy most about being a woman active in scientific research?

I like the fact that I can do what I’m passionate about. I like the fact that I’m happy to go to work. For me, my job isn't a place that I go, do a bit of work, and get paid at the end of the month. I like the fact that I’m never looking at the clock to see how many more hours I still have to work. I also appreciate the fact that scientists have the opportunity to change the world. No progress would be possible without science and committed individuals, nor would we be able to improve our quality of life. Nonetheless, it is sad to see how difficult it often is to find funding for our ideas. My dream would be to live in a society where science is treated like soccer is elsewhere, in that people would be willing to pay 200 million euros to bring a truly exceptional scientific star to their institute. In the world of soccer, this is completely normal. I have never been able to understand how people can pay such sums of money to someone literally chasing a ball for 90 minutes, whereas a scientist has to fight for an infinitely smaller amount of money just to develop a vaccine that could save millions of lives.

Working in science is an insecure job – at least until one becomes a professor. How do you deal with that or how have you done so thus far?

Science is a constant struggle and a constant search for a long-term position, which gives you the strength to perform fantastic work. On one hand, a steady place of employment relieves an enormous amount of stress, but on the other hand, it also introduces a different type of pressure. You are in a position that requires a never-ending effort to get financing for doctoral students, postdocs, and so on. You have many more duties and have to spend half of your time on bureaucratic and non-scientific matters.

How do you manage to strike a balance between such a demanding job and having a private life?

That’s a difficult question. I think that you need to be surrounded by people that support you. When I get home from work, I try to spend time with my child and not even touch my laptop until after bedtime, but after that I still have to catch up on all my work duties. This often takes me late into the night, and I get at most six to seven hours of sleep. Until I got my long-term position, finding a balance between my work and my personal life was quite difficult for me.

Do you have a role model?

Yes. My high school physics teacher, Caterina Benedict. Had it not been for her, I would certainly not be a scientist today. I did very well in physics, and she encouraged me and believed in me.

What would you like to share with young girls and women looking to pursue a career in science?

Take your time in deciding what you want. If you think that you really want to embark on a scientific path, wend scientists e-mails and ask them what you want to know. Perhaps the most important piece of advice that I could give would be: Even if you aren't entirely sure about what you want – if science is what makes you tick, then do it! Science is all about passion. If you're passionate about what you do, you will most likely succeed in everything you try! My passion and love for meteorology has kept me going for more than 20 years, despite all the frustrations and difficulties I have experienced along the way. So... JUST DO IT!

What is your research about?

In my research, I look at forests in the context of climate change. Trees and forests are extremely important for the Earth’s climate. One thing they do is absorb large amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it in wood and soil. Given that extreme weather events such as droughts and heat waves are becoming increasingly common worldwide, this important contribution to the Earth's climate is in danger. In my research, I primarily deal with the physiological processes: What mechanisms do trees have to outlast droughts? At what point will thresholds be reached where trees are truly damaged and in danger of dying out? These findings are incorporated into models to enable more precise projections, and this also helps us to find more resilient tree types for the future climate.

How did you get into research?

Nature has been a source of fascination to me since my school days, so I wanted to learn more about the interactions between air, water, plants, and soil. This led me to pursue studies in environmental science. Throughout my studies and while performing my thesis work in Ecuador, I noticed that I was keenly interested in trees and forest ecosystems. All of my subsequent research has been geared toward this field. Looking back on it, I can now see that my professional trajectory has been pretty linear. In addition to all the hard work, I had quite a bit of luck and fantastic women to look up to. For what it’s worth, I have only ever conducted research in working groups with women at the helm. Now, I get to oversee a working group, and that's a great feeling.

What do you enjoy most about being a woman active in scientific research?

I enjoy being able to explore my interests, work with trees and forests, think and find solutions for tricky problems, and work with students interested in this line of work. I work with colleagues from around the globe and often get to meet new people. My research lets me travel to fantastic places and affords me quite a bit of freedom.

At least until one becomes a professor, working in science entails a fair amount of professional instability. How do you deal with that or how have you done so thus far?

Of course, that is quite stressful, but I have a fundamentally positive outlook on things. So, I have always believed that things would work out, and if they don't, then I’ll just do something else. So far, this attitude has not misled me. Everything has worked out and, as of 2020, I have a permanent position.

How do you manage to strike a balance between such a demanding job and having a private life?

More often than not, that works out pretty well since the profession does permit quite a bit of flexibility. When you have young children, that is quite important. At the same time, the children help you to mentally disconnect a bit because weekends and evenings, they make sure that there’s always something going on – at least until they're in bed. I don't usually have that much time to worry about work or really think about much of anything else. There are times when the balance is bit a more tenuous, especially when I have pressing deadlines and need to take care of the kids’ schooling at home. That is indeed quite stressful.

Do you have a role model?

I don't have a direct role model, but I am generally impressed by women who exhibited strength in their scientific professions. One example of such is Marie Curie. Her energy and persistence in pursuing her research interests at the time – in spite of all the resistance she encountered – is truly impressive. Another female scientist whose biography I read and greatly enjoyed is Margaret Lowman, who is known in the USA as the “Einstein of the Treetops.” In her work, she was one of the first to systematically explore the treetops of rainforests and often – quite pragmatically – brought her kids along with her, assisting them later in their research when they were older. We can learn so unbelievably much from such women!

What would you like to share with young girls and women looking to pursue a career in science?

My first piece of advice would be to find a field that truly fills you with passion. Obviously, that doesn't usually take place overnight as you need to listen to yourself and of course try various things out. This might include, for example, doing internships, going abroad, and finding one's own style and interests. Even though researchers usually work hard and concentrate on a single topic, spending many lonely hours in the field, in the lab, and at the computer, the human element should not be underestimated. Having a strong network of colleagues is not only extremely important, but is also a source of incredible joy.